Question 2.0 – Is God a Warrior?

Sycamore Creek Church

May 29, 2011

Tom Arthur

Peace, Friends!

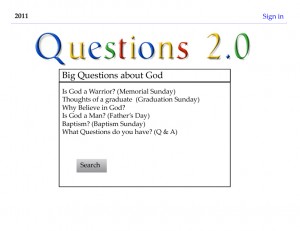

What questions do you have about faith, Jesus, God, Christianity, the church, and more? Probably a lot of questions. I do. Today we begin a series called Questions 2.0. We did Questions 1.0 last summer. It was based upon questions that our students asked me one day. Throughout that series, you submitted questions that I tried to answer on the last Sunday of that series. This series, Questions 2.0, is based on some of those questions that I’d like to go back and visit. I tried to answer those questions last year in three minutes or less so that we could cover more questions, but some of those questions deserved more than three minutes. That’s what Questions 2.0 is about. I’ve taken several of my three minute answers from last year and expanded them to a full sermon, but for the most part, they’re all questions you’ve asked me.

Questions 2.0 is also going to follow last year’s pattern with giving you the chance to ask some of your own questions again. Each Sunday you’ll be given the opportunity to submit questions that I will attempt to answer on the last two Sundays. Yes, last two Sundays. That’s because the second to last Sunday is baptism Sunday, and I’d like you to submit your questions about baptism for that Sunday. On the last Sunday, though, any question is free game. So email them to the office and we’ll compile them. My questioner that Sunday will be Kahla Arvizu who is a prosecuting attorney in Lansing. Yikes! I’m sure she’ll do a great job of asking me the questions you submit. Kahla will be picking the questions, with a little help from some others, and I won’t see them ahead of time. So ask away!

On to today’s question: Is God a warrior? Today is Memorial Day, and it seemed appropriate to tackle this question about God and war on this Sunday. It’s a great question. I get asked it in a lot of different forms. One of the most common is asking about how to reconcile the “God of the Old Testament” and the “God of the New Testament.” It appears to many that God is very angry and vengeful in the Old Testament and loving and merciful in the New Testament. So which is it? Is God a warrior or a lover? Is God angry or alluring? Is God mean or merciful?

Christians have been arguing about this for a long time, and even though I’ve expanded this question to an entire sermon, it won’t be all wrapped up when we’re done. But I do hope you’ll have a better understanding and appreciation of some of the issues that arise when you start asking about God and war.

On one side of the conversation Christians often point to the classic verse in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Jesus says, “But I say, don’t resist an evil person! If you are slapped on the right cheek, turn the other, too” (Matthew 5:39 NLT). Turn the other cheek. God is a lover, and a rather peculiar one at that. Case closed. Right? Well, not according to the other side of the conversation. Other Christians want to point to Paul (among many other passages) when it comes to war and Christians. Paul says, “The authorities are sent by God to help you. But if you are doing something wrong, of course you should be afraid, for you will be punished. The authorities are established by God for that very purpose, to punish those who do wrong” (Romans 13:4 NLT). God is a warrior. Case closed. Right? Well, let’s explore this issue further.

I’d like to bring into conversation two mentors of mine from past days: C.S. Lewis and Martin Luther King, Jr. They were roughly contemporaries although they lived in different countries and King was quite a bit younger than Lewis. Lewis writes in the context of WWI (in which he fought as a soldier) and WWII while King writes in the context of the Civil Rights Movement. They both have significantly influenced my Christian walk, but they disagree on this issue of God and war.

C.S. Lewis – Why I Am Not a Pacifist

In an essay titled, “Why I Am Not a Pacifist”, C.S. Lewis explains why he can’t buy into a God is a lover and not a warrior ideology. He does so on four fronts: Fact, Reason, Authority, and Emotion. Let’s look at all four.

Facts

On the facts side of things Lewis points to the difficulty in actually getting to the facts of what good or bad war actually does. He agrees that war is disagreeable, but he does not believe that it can be proved historically or any other way that “wars always do more harm than good.” To suggest such is speculation, and on the contrary, Lewis finds that “history is full of useful wars as well as useless wars.” These are the facts on the ground for Lewis.

Reason

Lewis then explores what he is best known for: Reason. Lewis brings up several reasonable strikes against pacifism. First, being against war implies a kind of materialistic world-view. A pacifist believes that pain and suffering are the greatest evils, but they are not. A Christian holds a spiritual worldview and believes that there are some things more evil than dying.

Second, Lewis points out that only “liberal” (or Democratic) societies tolerate pacifists. If you were in a totalitarian society or a dictatorship, you couldn’t be a pacifist. So ultimately, pacifism would lead to a totalitarian takeover of the world. Democracy would come to an end.

A third reasonable strike against pacifism, Lewis tells us, is that pacifism assumes that a kind of utopian society is possible. Pacifists believe that if only we all loved one another, then there wouldn’t be any evil or suffering in the world. Lewis is skeptical of this utopian ideology. Lewis concludes, “I have received no assurance that anything we can do will eradicate suffering.”

Authority

Having explored facts and reason, Lewis turns to authority: human authority and divine authority. By “human authority” Lewis means the authority of thinkers throughout history who may or may not have been Christians. Lewis believes that “general human authority” over all time “echoes with praise of righteous war.”

Being a Christian, Lewis looks to more Christian forms of authority: divine authority. He points out that the Church of England’s own articles of belief allow for war. He then walks back through history and points out that Thomas Aquinas, the most significant Catholic theologian, allowed for war. Continuing backwards, he points to St. Augustine who is very well known for his “just war” theology. He believes that all of these are silent or speak against pacifism.

Lewis then looks at the divine authority of the Bible. He says that pacifism is based primarily on one verse about turning the other cheek (Matthew 5:39). He points out that if you take “turn the other cheek” to such a literal extent, you are obliged to take the rest of Jesus’ sayings with such rigor and extent, but “turn the other cheek” is intended to be about and limited to neighborly disagreements where the only motivation is retaliation or revenge. Thus, “Insofar as you are simply an angry man who has been hurt, mortify your anger and do not hit back.” Lewis points out that there “may be then other motives than egoistic retaliation for hitting back.” Lewis also points out that Jesus praised without reservation a Roman Centurion, and Paul (Romans 13:4) and Peter (1 Peter 2:14) speak in favor of following governmental authorities even into the throes of war.

Emotions

Lewis throws one more salvo at pacifism pointing out that “pacifism threatens you with almost nothing…it offers you a continuance of the life you know and love, among the people and in the surroundings you know and love.” Pacifists get to stay home while everyone else goes off to war and endures the hardships of war.

To sum things up, Lewis says, “If I tried to become [a pacifist], I should find a very doubtful factual basis, an obscure train of reasoning, a weight of authority both human and divine against me, and strong grounds for suspecting that my wishes had directed my decision.”

Martin Luther King Jr. – An Experiment in Love

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a Baptist preacher who was influenced by the methods of Gandhi. He did not like the word “pacifist” and so he adopted the phrase: active nonviolent resistance. Although he points out that when the Civil Rights Movement began, it was squarely based in the church and the methods that they used were simply referred to as “Christian love.” In a brief essay titled “An Experiment in Love” King outlines six points of active nonviolent resistance.

Active Not Passive

First, there is nothing passive about what King and his fellow Christians and associates were up to. He says that “Nonviolent resistance is not a method for cowards; it does resist…It is not passive non-resistance to evil, it is active nonviolent resistance to evil.” When you watch videos of civil rights demonstrators resisting fire hoses and German shepherds, you most certainly cannot call them passive cowards.

Reconciliation and Community

Second, King points out that the ultimate goal of active nonviolent resistance or Christian love is reconciliation and community. Active nonviolent resistance “does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding…The end is redemption and reconciliation.” In fact, the end is what King always had in mind. It was the end that determined the means. King could have given in to other more aggressive approaches to the civil rights movement like those of the young Malcolm X, but King believed that this would put too many obstacles in the way of friendship and community. King referred to this vision of community as “the beloved community.” He always kept the beloved community in mind with whatever methods he used to accomplish it.

Against Evil

Third, King saw that active nonviolent resistance “is directed against the forces of evil rather than against the persons who happen to be doing the evil.” King didn’t see white people as the primary problem. He saw evil as the problem. He could in essence “love the sinner and hate the sin.”

Redemptive Suffering

Fourth, Active nonviolent resistance “is a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation, to accept blows from the opponent without striking back…Unearned suffering is redemptive.” Most certainly the suffering that many civil rights protesters encountered was unearned. Most of us today would say that they were seeking only to have their basic rights recognized. The right to vote. The right to be accorded human decency and standards. Their attempts to get these rights through active nonviolent resistance or methods of Christian love earned them suffering. In this way, they imitated their savior, Jesus Christ, who was sentenced and crucified although he lived a perfect and sinless life.

Agape Love

Fifth, King points to not just one verse in the Bible but the general character of God’s love as displayed in the entire Bible and especially in the person of Jesus Christ, God’s son. This kind of love is called agape love or unconditional love. Agape:

is a love in which the individual seeks not his own good, but the good of his neighbor (1 Corinthians 10:24)…Agape is love seeking to preserve and create community…The cross is the eternal expression of the length to which God will go in order to triumph over all the forces that seek to block community. The resurrection is a symbol of God’s triumph over all the forces that seek to block community.

God’s love is most fully seen in Jesus’ sacrificial death on the cross. He did more than just turn the other cheek. He took the sins of the world upon himself and died so that we might be made right with God. This is the highest form of love.

God Wins

Sixth and last, King points out that in the end God wins. Active nonviolent resistance “is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice.” He liked to say that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.”

In summary, King believes that:

To meet hate with retaliatory hate would do nothing but intensify the existence of evil in the universe. Hate begets hate; violence begets violence; toughness begets a greater toughness. We must meet the forces of hate with the power of love; we must meet physical force with soul force. Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding.

So Who Is Right?

Naturally at about this point you’re probably asking yourself, “So who is right?” Great question. Let me tell you. No. Just kidding. I think both of them get parts of it right and parts of it wrong, although I tend to think that King gets more of it right than Lewis does. Although, remember that I am a Christian today because of Lewis. I deeply respect him, and I continue to learn from him whenever I read what he has to say, but I think there are some significant things he gets wrong in this conversation.

Where Lewis Gets It Wrong

Contrary to what Lewis says about “pacifism”, the kind of active nonviolent resistance that King advocates for is not based on a materialistic worldview that believes that death is the greatest tragedy. King believed that failing to love is the greatest tragedy. King believed and expected that his beliefs and methods were worth dying for. This makes Lewis’ implied slam on “pacifists” that they are cowards seem rather hollow.

In terms of divine authority, Lewis ignores the great Anabaptist Christian traditions of pacifism in his assessment of pacifism. Anabaptists who are modern day Mennonites and Amish have a long history of understanding the Christian faith as essentially nonviolent in nature. Lewis also seems to ignore entirely some very early Christian writing about war. In the Apostolic Tradition, a third to fifth century church membership manual, new converts were not allowed to be in the military if they were expected to kill other people.

There is one last area where Lewis gets it wrong. He believes pacifism is based almost entirely on one verse about turning the other cheek. Lewis ignores the entire character of God as especially seen in Jesus’ willingness to die on a cross without retaliation to his executioners. He even forgave them and us!

Where Lewis Gets It Right

While Lewis gets a lot wrong in this conversation, I think he does get at least one thing very right. Pacifists, even non-violent active resisters, do at times have a very utopian ideal that is most likely unrealistic. I doubt that we will ever eradicate suffering in our world. King himself had this kind of unrealistic optimism at times. As a kind of correction to this fault, my friends who are hard core Christian “pacifists” today will talk about being faithful to Jesus’ ways whether they are successful or not. They believe the fruit of their active nonviolent resistance is up to God. Their job is just to faithfully follow in the way that Jesus lived.

Where King Gets It Wrong

While I lean toward King in this conversation, there are several places where I still have questions about whether King gets it right. Active nonviolent resistance assumes a conscience within the enemy. King believed that what the civil rights movement would do is spark the conscience and soul within the white community. He was right in many ways. But what if the enemy is pure evil? What if the enemy has lost all sense of conscience?

A second question I have for King has to do with the media. Active nonviolent resistance is dependent upon modern media to showcase the injustice. King saw the media as a tool to spark the conscience of the nation. They would see on TV exactly what was happening: fire hoses and dogs being trained on nonviolent resisters. This method was very successful in its day (and we even saw the success of this in the recent conflicts in the Middle East where the internet allowed the world civilian to see what was happening around the world). But what about times and places before modern media?

Another question I have for King has to do with his methods applied to international conflict. Active nonviolent resistance was used primarily within a nation, but not between nations. How effective is it in international conflicts? King began to speak out against the Vietnam war toward the end of his life, and this made him very unpopular especially among his fellow civil rights leaders, but he did not have time to flesh out fully what active nonviolent resistance would look like if used in conflict between nations.

Lastly, while active nonviolent resistance “won” the civil rights legislation battle, did it accomplish the reconciled beloved community between blacks and whites that King had hoped for? In some ways I think it did, but in other ways I’m not so sure. It certainly did keep more obstacles from being put in its place. Consider the obstacles that the IRA has put in place for community within Ireland, and you see the benefits of King’s methods. But I don’t think we’re anywhere near ultimately fulfilling King’s dream of the beloved community.

Where King Gets It Right

In the end, I think King gets it right more often than Lewis does. Active nonviolent resistance is not cowardly, but at its highest, requires perhaps more courage than violent resistance. Do you have the courage to offer your body as a sacrifice to a higher good? Do you have the courage to believe that suffering and death in this life is nothing in comparison to the life to come? King was no coward. He sacrificed his life for the good of the beloved community.

Second, active nonviolent resistance is more in keeping with the entire character of the gospel as especially seen in the incarnation, cross, and resurrection. If we know God most fully in the person of Jesus, then ultimately the question of how to reconcile the “God of the Old Testament” and the “God of the New Testament” (which by the way I do not think there is an ultimate difference between the two) must come in the person of Jesus. We know God most fully in Jesus, and in Jesus we see the heart of God’s love most fully on the cross.

Lastly, active nonviolent resistance rightly believes that in the end, God’s justice will win. We know how the story ends. God wins. As Rob Bell says, Love Wins. As I preached in the last series, forgiveness wins. If God wins in the end, then we must be willing to follow God even when it looks like God is not winning. As King says, the arc of the universe is long and it is bent toward justice.

Does this resolve every question when it comes to God and war? No. Does it raise more questions? Yes. Perhaps the worst thing we can do is ignore and disregard those who disagree with us on this issue. I encourage you to continue in conversation with others who may see our Christian life in a different light. If you lean toward Lewis, talk to a King. If you lean toward King, talk to a Lewis. In the end, I believe that if God is a warrior, then he is more like the kind of warrior who gives his life that his enemies and friends might have community and friendship. That’s a strange warrior. That’s a strange lover too!

[…] Memorial Day, I preached a sermon comparing C.S. Lewis and Martin Luther King Jr. and their various perspectives on war. I adapted […]